The science and sophistication behind SRA’s efforts to produce new sugarcane varieties for commercial release

Most people involved in the Australian sugarcane industry are familiar with the end-product of Sugar Research Australia’s efforts to release new varieties to industry each year for commercial use. However, less is known about just how SRA actually produces new genotypes for testing in its selection programs. Read on below, as we shine a light on this meticulous process – beginning with the creation of new genotypes through cross-pollination.

Magic at Meringa

Tucked away off the Bruce Highway south of Cairns, in Queensland’s Far North, SRA’s Meringa Station has been the main variety breeding facility for the Australian sugarcane industry for almost 100 years. It’s here, amongst its unassuming buildings, photoperiod facilities, laboratories and trial plots, that the intricate work of creating new, commercially-viable sugarcane varieties for Australian cane growers and millers takes place. Developing new cane varieties, with superior productivity and agronomic traits such as high yield, sugar content (CCS) and good resistance to disease, is central to helping the industry to remain productive, sustainable and profitable. However – as with most significant scientific breakthroughs – producing a new variety that outperforms existing, commercially-proven varieties, takes many years of experimental genetic crossing, research and development.

Only the best progress

At any one time, more than 70,000 experimental clones are under trial at various stages of selection at the experiment station. However, of these, only an elite few will progress through to commercial release; after approximately 13 years of rigorous testing, trial work and industry endorsement. Here, we give an insight into the complex work undertaken by SRA’s dedicated Variety Development team, to bring the best-of-the-best varieties to commercial evolution.

Where it begins – The crossing station

The journey to develop a new sugarcane variety begins at Meringa by creating new genotypes (or individuals with different sources of genetic variation) through cross- pollination of existing sugarcane varieties used as parents, varieties which have the breeding potential of passing on their favourable traits to their offspring. SRA’s parent population includes previous and current commercial varieties, experimental clones which never made the commercial grade but are ideal parents, elite clones from each of SRA’s regional selection programs, international varieties, and Introgression clones containing wild genes. Approximately 2,500 parents are maintained either in one of SRA’s climate-controlled photoperiod facilities, or infield, in one of the station’s numerous ‘arrowing’ or flowering blocks or in a parent holding block (while parents’ offspring are being trialled to assess the future use of a parent).

However, not all 2,500 parents are used annually

“Generally, we inspect up to 500 parents two to three times a week, depending on if we are doing field or photoperiod (PF) crossing,” Northern Variety Development Manager Dr Felicity Atkin explains. “We look to see which parents are flowering, and how many flowers we’ve got of each of those parents. What we are looking for is when the anthers at the top of the flower are just starting to open. That’s when we know the parents are ready for crossing,” she said. Once the parents are assessed, available flowers of each parent for that day are recorded in SRA’s plant breeding database called SPIDNet, by scanning a barcode assigned to each flower on a mobile device.

A tiny, botanical gender reveal

Florets from the flowers of selected parents are brought back to the laboratory at Meringa Station to determine if the parent will be used as a male or female. This is determined by how much viable pollen a flower produces. To do this, anthers containing pollen are extracted from the florets and placed onto slides where the anthers are squashed to release the pollen. A basic starch test using a drop of potassium iodide is then conducted on the pollen grains. An assessment of the percentage of viable pollen present under a microscope is used to determine the gender. A parent that produces more than 20 percent viable pollen is considered a male, and any less it is used as a female. This process is conducted each time a crossing session is carried out at the station, as pollen viability is sensitive to nocturnal temperatures, and male sterility is often experienced when night-time temperatures drop below 18 degrees Celsius. These changes in pollen viability often results in some parents being used as both a male and a female at different times during a crossing season.

Shuffling the genetic deck

“Once we know what males and what females we have, we use various types of information, to determine which of those parents we match together,” Dr Atkin said. “This information includes the average breeding value of two parents as potential cross combination, that is, their potential to pass on their favourable genes to their offspring, such as cane yield, sugar content and disease resistance. “We also use pedigree information, as we don’t want to match close relatives together, such as brothers and sisters. This part of the process is very important as the more distantly related two parents are, the more variation we get. “Pollen compatibility between two parents is also an important consideration – we want to make sure the male parent is strong enough to pollinate the female parent to maximise seed viability after pollination. “Previous success of a female by male combination is also used in our assessments (including how many offspring have made it to the final assessment selection stage or to commercial release). Current seed availability is also considered, as there is no sense in wasting valuable/limited flowers if a cross combination is currently available in good quantities. “And finally, we also consider, is the cross combination wanted by one or more of the selection programs? A list of commissioned crosses from each of SRA’s regional selection programs is used to guide the cross-selection process.” By crossing two parents together, this reshuffles the genes of each parent to create new sources of genetic variation, which creates the seedlings that form the basis or starting population of SRA’s variety selection process.

The Crossing Process – Where the Magic Happens at Meringa

Once the cross combinations (or the happy couples) are selected, the flowers are then arranged together in SRA’s crossing paddock (or ‘the honeymoon suite’ as it is affectionately known by SRA breeding staff). Before the male and female flowers are placed together, the female flower is inspected once more, and any open florets are plucked off just in case this female plant has already been pollinated in the field, to ensure controlled pollination will occur.

“It’s very important to trace the pedigree of each of our crosses as this information is used to assess the breeding value of a parent, so bringing the female flowers back to a virgin state by plucking off any open anthers is crucial. We want to make sure we know which male has pollinated which female,” Dr Atkin said.

Matchmaking in the honeymoon suite

Each cross is then carefully arranged in a fabric hanging lantern for controlled pollination and tied together, with the cut stalks of each flower placed into a crossing solution to keep the flowers alive for up to eight weeks during the pollination and ripening processes. The male flowers are also placed approximately one foot above the female flowers, so that the male flowers’ pollen dusts the female flowers when they shed pollen, to maximise the fertilisation process and seed viability of each cross.

Once the crosses are arranged, the lanterns are then tied shut to ensure controlled pollination takes place. This is to prevent the pollen from any (unwanted) male flowers accidentally contaminating and pollinating the female flowers, resulting in an unwanted or undesirable match. “By crossing parent A with parent B, we are re-sorting the genes and creating new (and ideally improved) sources of genetic variation, from which we then select to grow as the start of our SRA selection programs across the regions,” Dr Atkin said. “On average we make approximately 1,000 unique cross- combinations each year, and in a good year we can make as many as 2,500, but we tend to focus on quality rather than quantity.”

During the cross- pollination process, the plants are kept inside the lanterns for two weeks. This is how long it can take for each flower to open up and for complete pollination to occur. After two weeks, the male flowers have done their job and are discarded. The female flowers are also removed from the lantern so the lantern can be used for another crossing. But the females are kept alive for an additional three to six weeks to allow the seed to mature for ‘good seed set’, that is, a healthy number of viable seeds to generate the initial selection population for the start of the selection program. Before that happens, the variety breeding team assesses each cross to see how much viable seed has been produced.

Evaluating seedling success

Once the seed from each female flower has matured, the flowers are harvested in the crossing paddock, stored in muslin bags and dried down for a minimum of four days in Meringa’s de-humidifying chamber at 11 degrees Celsius and 13 percent humidity. Once dried, the seed can be harvested from each female flower and the breeding team can start evaluating just how successful their crossing efforts have been. “The process starts by weighing the seed from each cross and anything yielding more than five grams of seed we will take a one gram sample from and perform a germination test on them,” Dr Atkin explains. “Based on that germination test, we will determine either how many bags of seed we will get per cross, or whether we discard that cross. Generally, we discard up to 30 per cent of the crosses that we make, just because the percentage of viable seed is too low or there was no pollination at all.” The viable seeds are vacuum packed and stored in SRA’s seed freezer at -20 degrees Celsius where they can remain viable for future use. This seed will be used to produce the starting population for the first stage of the selection program.

“From the crossing work, we select the best crosses to germinate approximately 100,000 seedlings which are all genetically unique to start the selection process,” Dr Atkin said. “So, the elite cross combinations will potentially be the source of new commercial varieties released in 13 years’ time.”

Germination – The start of the selection process

Each year, seed selected from the most recent crossing efforts are germinated in the Meringa, Ingham, Burdekin and Mackay stations to produce starting populations for the Northern and Herbert (Meringa), Introgression (Ingham), Burdekin (Ayr), and the Central, Southern and New South Wales selection programs, respectively. Sugarcane seed (also known as fuzz) are spread onto the surface of trays of seedling raising mix, sprayed with a fungicide and watered in where they are then covered in plastic to create a warm moist microclimate in a germination chamber at approximately 32 degrees Celsius for a minimum of two days. This creates the ideal conditions for sugarcane seed to germinate. After two days the seed has germinated, and the trays of germinated seedlings are then moved to the glasshouse where they continue to grow and harden. After four weeks’ growth the seedlings are large enough to transplant into bigger trays as family groups and are moved to the seedling rearing benches outdoors to continue to harden. This means that each tray of seedlings represents 20 siblings from the same female by male cross combination, that is, they are all brothers and sisters who share common parents but are all genetically different. The number of trays per family transplanted depends on whether it is a proven family or not. Once out on the benches, the seedlings are watered three to four times a day, and excess leaf material is trimmed once a week to harden the seedlings and promote tillering.

The Selection Program – Where the Magic is Realised

The selection program – assessing families in PATs

Once seedlings produced through SRA’s crossing program reach three or four months of age, they are strong enough to transplant to the field in family plots as part of the first stage of the selection program. These are called Progeny Assessment Trials (PATs). This is where all sugarcane genotypes start their 12-year journey towards possible commercial release.

Keeping it in the family

The PATs are grown in the North, Burdekin and Central regions, as each region has different incidences of pests and diseases, as well as climatic conditions, including rainfall. As sugarcane seedlings are germinated from true sugarcane seed, this means each plant (or seedling) is a genetically unique individual, and families are replicated in PATs, but individuals aren’t. Assessing individual seedlings at this stage is inefficient, so seedlings are assessed by their family performance instead. Each ‘family’ plot assessed includes seedlings which are full- siblings (like brothers and sisters), produced from the same cross (female by male cross combination), allowing between and within family selection during the PAT stage.

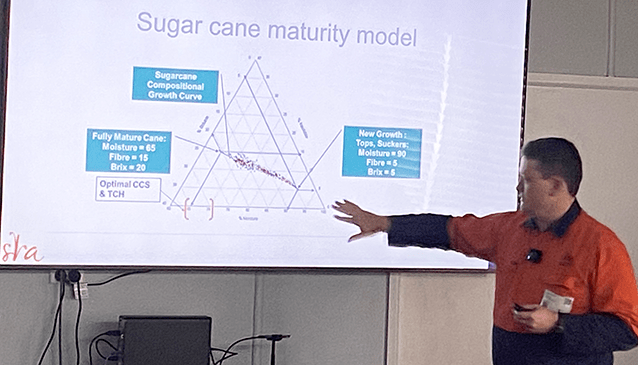

The PATs are grown for 12 months in the plant crop and harvested at maturity to assess each family’s commercial potential for cane yield (tonnes cane per hectare – TCH), sugar content (Commercial Cane Sugar – CCS) and fibre content (% fibre). At the same time each family is assessed visually for undesirable traits, including suckering, lodging, and flowering propensity, presence of diseases including smut and leaf diseases, and tiller height and number. More specifically, TCH is assessed for each sugarcane family in PATs on a plot-mean basis. The cane from each plot is weighed at harvest using a commercial cane harvester and an SRA in-field weigh unit. At the same time, a sub-sample of sugarcane stalks is hand-cut from each plot and processed through SRA’s SpectraCane using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIR) technology to assess CCS and fibre content.

The PATs are then ratooned for selection the following year. The best performing families are identified based on the analysed plant crop data (family selection). Individuals from within these top families are then visually assessed for ratooning ability, vigour, stalk number and diameter, canopy structure and health, flowering, suckering and lodging propensity, and side-shooting at first ratoon (1R) harvest. Only the best-looking individuals are selected to progress to the next selection stage (within-family selection).

Time to shine – Trial stage 2 – CAT assessment

The top seedlings from the PATs are planted in the next stage of the breeding process, known as Clonal Assessment Trials (CAT). This is also known as the first clonal stage, as this is the first time an individual is planted and assessed in a uniform plot consisting of just one clone. Approximately 10,000 clones make it to CAT stage and are planted across the same sites as the PATs – North, Burdekin and Central. It is at this stage a name is assigned to clones. Each unique clone name indicates the region and year of its first planting to the field as a seedling.

Like the PATs, each clone is assessed in CATs for TCH, CCS, fibre content and visual appearance in the plant crop. Initial selections are made based on this plant crop data to select which clones are sampled again for CCS and fibre content in the first ratoon (1R) year (all clones are assessed for TCH in 1R), and which clones are sent for their first smut and Pachymetra screening. Any smut or Pachymetra susceptible clones or clones with poor CAT performance are discarded and only the top clones progress to the final stage of selection.

Final countdown – Trial stage 3 – FAT chance

The final trial stage in the breeding program is the Final Assessment Trials (FATs). FATs are undertaken across all six sugarcane growing regions of Australia – North, Herbert, Burdekin, Central, South and New South Wales. From the CATs, only 500-800 clones progress through to the final stage. Within each region, approximately 150 new clones are planted across three or four FATs on commercial farms grown under Best Management Practices. These represent each region’s main production areas and growing conditions. More intensive testing is undertaken at the FAT stage. Each clone is assessed for TCH, CCS, fibre content, visual appearance, and its ratooning ability up to second ratoon (2R).

Clones are also retested for smut and Pachymetra. Elite clones are identified based on their initial performance in FATs and disease ratings. They are then established in a repeated series of FATs to assess clones under different growing years, and screened for further diseases including leaf scald, Fiji leaf gall, mosaic and red rot. Their millability is also assessed by testing their fibre and sugar quality. At the same time, the most promising clones are being prepared for possible future release by starting the ‘bulking up process’.

And the winner is! Progressing a variety to commercial release

From the FATs, a select number of elite clones are submitted each year to Regional Variety Committees (RVCs) for consideration for commercial release. There are six RVCs in Australia, each committee comprising of grower and miller voting members. The committees are also supported by non-voting growers (particularly those that host SRA trials), technical staff from milling companies, private agronomists, productivity services organisations and SRA staff. Each release decision requires a unanimous vote. At annual RVC meetings, each committee is presented with detailed data from new candidates compared to the relevant commercial varieties of that region. The commercial merit of candidate varieties is considered against the local production constraints and challenges, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of the current variety mix. Yield and CCS across crop classes and trial locations is a key focus. The weighting of TCH and CCS reflects the whole of industry relative economic value which is region-specific and based on the local drivers of cost and revenue. Other characteristics that affect the agronomic fit of varieties are also considered including lodging, flowering, suckering, side-shooting, germination behaviour and early vigour. Disease ratings are also key. Once a new variety is approved for commercial release, it is added to the Approved variety list for the region.

The use of an Approved variety is seen as meeting one aspect of every grower’s General Biosecurity Obligation under the Queensland Biosecurity Act (2014). Cane supply agreements also commonly reference delivery of only Approved varieties.

Variety Guides

All new varieties approved by Regional Variety Committees (RVCs) for commercial release are added to SRA’s Regional Variety Guides when they are updated each year. The Variety Guides contain detailed information on each variety that has been approved for each Region. Regional guides are designed to help growers across the industry with their agronomic considerations when selecting new varieties to plant and trial on their farms. The guides are updated annually, with information that comes from the best available data of regional variety performance and disease ratings.

The 2025-26 SRA Variety Guides are currently being compiled. Previous year’s guides can be found on the SRA Varieties web page.

This story first appeared as a two part series in Cane Matters Summer 2024/25 and Cane Matters Autumn 2025. The magazine editions can be accessed here. To subscribe to Cane Matters and other SRA news, sign up here.